Extracts from The Writer's Room Interviews

Some brief extracts - subscribe here to read all the interviews in full.

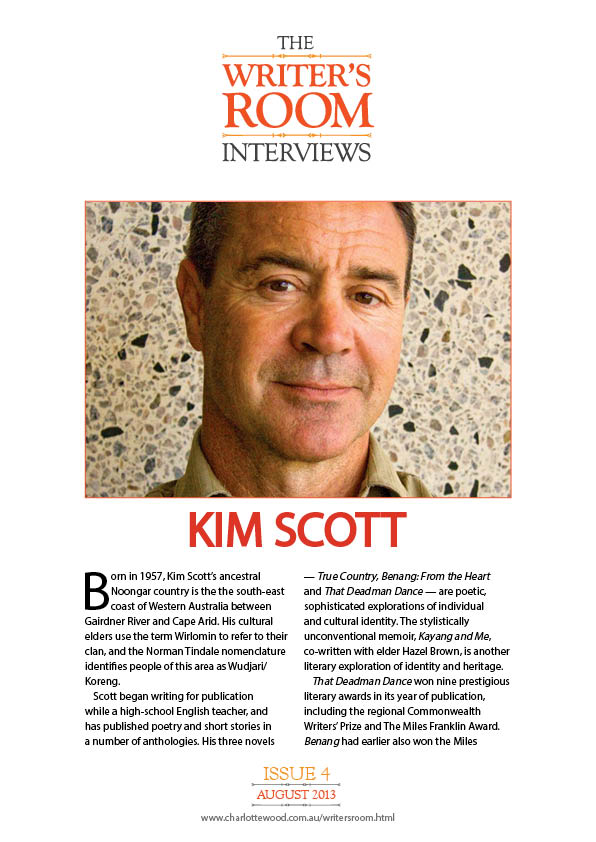

ISSUE 4: KIM SCOTT

ISSUE 4: KIM SCOTT

On routine

"Most recently the routine was four to six hours at the beginning of the day. Quite often it’s good for me to do some exercise early on, to trim off some of the nervous energy and help me get a little bit more mellow, rather than all edgy. It makes it easier for me just to sit, and takes a bit of the edge off things. So there’s a set time, or sometimes it’s word count — I keep a bit of a tally — or number of pages, I just keep an eye on that, so I’m not getting too slack, not just spending six hours at the desk gnashing my teeth."

On ego

"I think it’s a small ego that’s required, but it’s such a complex thing. It’s cunning and slippery. I think of some people I know who’ve got big egos, and they want to be writers. They’ve written books that no one will publish, and I think it’s all ego driving them. They believe these are really good books even though everyone tells them they’re not, and they want you to read them, they insist that you read them — all that sort of thing. I haven’t got that sort of ego, and I don’t think that’s the sort that goes with actually doing the writing. I think the preparedness or the readiness to make yourself vulnerable, and move into areas that not a lot of people necessarily want to go — I think there’s a lack of ego in there, and I think there’s courage in there. I think when ego does come into it is in thinking, ‘I want to do this really well. I want to do a good job.’"

On prizes

"There’s a writer I admire, though I haven’t read much of his stuff: Eduardo Galeano. There’s a line in one of his lovely essays, ‘In Defence of the Word’: ‘Mistrust applause; it may mean you’ve been rendered innocuous.’"

ISSUE 3: MARGO LANAGAN

ISSUE 3: MARGO LANAGANOn starting out

“I embarked on the huge Fantasy Brick… it’s an exercise in over-world-building. [laughs] I built this incredible series of cultures and histories and wars and communities and landscapes, and it just got to the point where I couldn’t move a story through it. I just couldn’t keep track of it. I worked on that for about three years, toiling away, going past my deadline year after year. In the end I threw up my hands and ran away to Clarion West, a six-week short-story workshop for science fiction and fantasy writers in America.

On breaking through

And that’s when I decided, ‘This is never going to happen. I am obviously not ever going to make a living as a writer, so just stop thinking of it like that. Just write the stories that are demanding to be written, rather than thinking of an idea and then thinking: audience, okay how do I pitch this to them?’ I decided to just write the stuff that needed to be coughed up, vomited up …That was how the stories in Black Juice mainly got written—and they were the ones that really started working for people, because I was putting more of myself into them.

On routine

I sit down and I write ten pages in a day. And then I stop and I try to leave it at an interesting place—I try not to leave it at the end of a scene, so I don’t have to grind myself into gear the following morning to start on something new. For a short story, for example, I’ll write right up to just before the climactic thing. I’ll know exactly what’s going to happen, and I’ll be itching to make it happen but I know I haven’t got the puff to do it today. So I’ll stop, and leave myself the treat of finishing tomorrow, knowing that I’ll do a better job of it first thing in the morning.

On fear

No, not any more. I’m not fearful... When I got to the end of my draft, that was the only time I would let myself go back and reread. And then, rereading the whole thing, I couldn’t spot the days that had been so bad. I realised my feelings are completely unreliable when it comes to judging my own work at that level, from the middle of it. I just forge on, and then come back later and see the thing as a whole. I don’t really even bother now, thinking ‘I wrote terrible stuff, I wrote shit’.

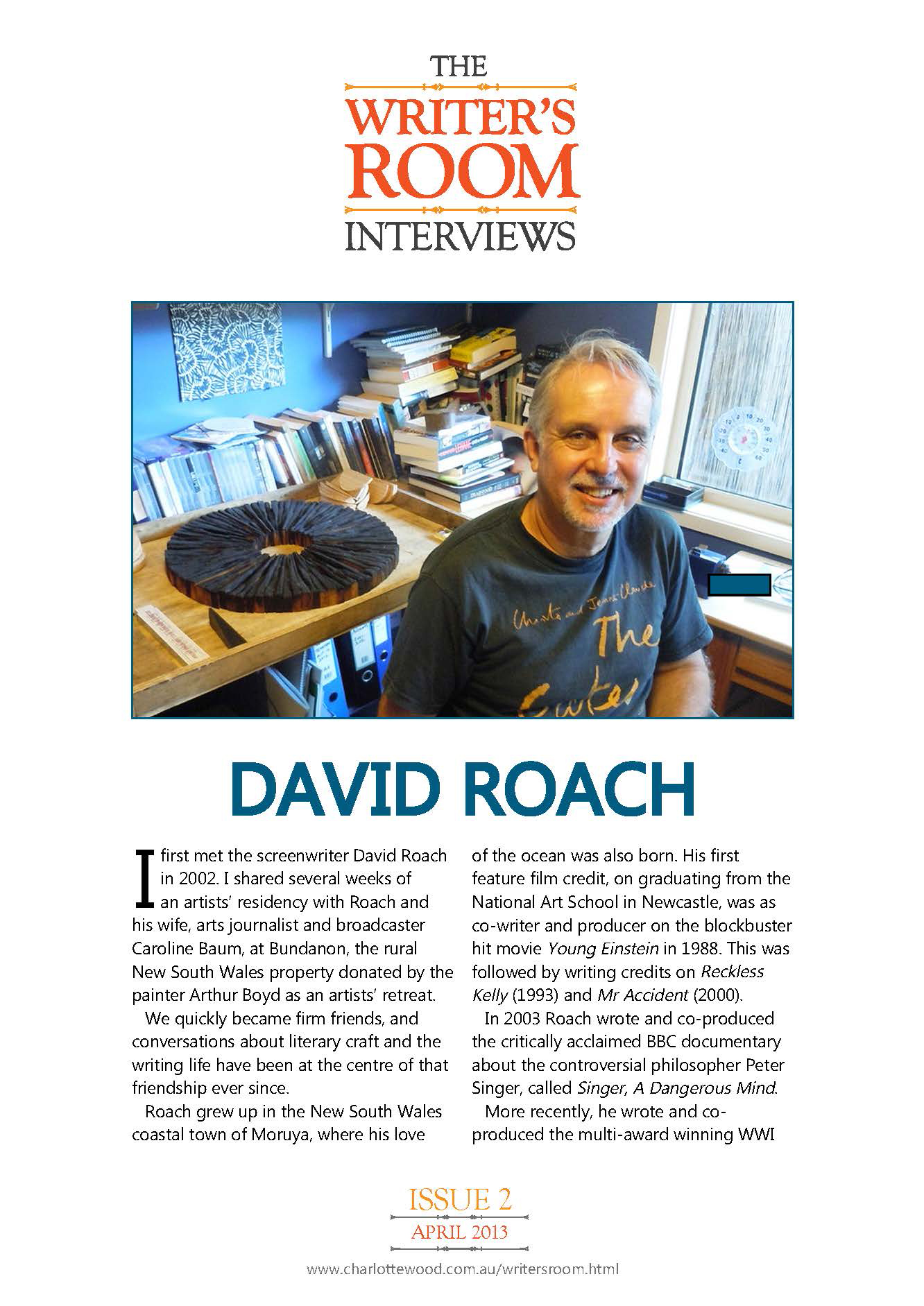

ISSUE TWO: DAVID ROACH

The award-winning Australian screenwriter, David Roach, grew up in the New South Wales coastal town of Moruya, where his love of the ocean was born. His first feature film credit, on graduating from the National Art School in Newcastle, was as co-writer and producer on the blockbuster movie Young Einstein in 1988. Most recently he wrote and co-produced the multi-award-winning WWI feature Beneath Hill 60 (2010). His newest release is the feature-length documentary narrated by Russell Crowe, Red Obsession, which screened at the 2013 Berlin and Tribeca film festivals ahead of its Australian cinema release in August.

Roach is fascinated by the craft of storytelling and speaks thoughtfully about its complexities, always rejecting the mechanistic, instruction-book tone that often pervades other discussions of story structure.

The award-winning Australian screenwriter, David Roach, grew up in the New South Wales coastal town of Moruya, where his love of the ocean was born. His first feature film credit, on graduating from the National Art School in Newcastle, was as co-writer and producer on the blockbuster movie Young Einstein in 1988. Most recently he wrote and co-produced the multi-award-winning WWI feature Beneath Hill 60 (2010). His newest release is the feature-length documentary narrated by Russell Crowe, Red Obsession, which screened at the 2013 Berlin and Tribeca film festivals ahead of its Australian cinema release in August.

Roach is fascinated by the craft of storytelling and speaks thoughtfully about its complexities, always rejecting the mechanistic, instruction-book tone that often pervades other discussions of story structure.

On starting

Being a surfer, I’ve always been a morning person. I find the best time for writing is often the best time for reading. And I’m a much better reader in the morning, I’m more efficient, I can absorb more. So if I am in the middle of a project I start work as early as possible—about six or seven. The time from sleep to writing should be as uninterrupted as possible. I try to protect that liminal state, when you are on the threshold—somewhere between being asleep and fully awake, before the world has had a chance to intrude — I try to extend it for as long as possible because it can be the most creative time of the day.

On ‘the single arena’

For thousands of years, storytellers have looked for a unified or single arena in order to

contain a story and keep the pressure on. I think about an ‘arena’ as like a city surrounded by a city wall. There are so many places you can travel to in a film that you tend to go there ... but when you do this, sometimes your story can end up feeling sort of dissipated and episodic. Creating a single arena of the story allows you to keep the pressure on that story — because every time you change the arena you dissipate the energy. You’ve got this new level of interest, but the energy of the story can fall away because you have to develop new relationships again — relationships of the characters to the landscape, to other characters. You are building from ground level again.

On dialogue

In film, dialogue is the best way of expressing the values of your characters. But dialogue can be a double-edged sword, because you can get lost in it. You can look at a story that’s not quite working and you can spend days and weeks rewriting the dialogue, and it doesn’t make any difference to the story. It’s still not working, even though the dialogue is sparkling. And the reason it doesn't work is to do with a much deeper thing, which is structure. The most important thing of all in dialogue is not the text at all, but the subtext. That’s where the deeper meaning is conveyed. You’re not looking at what the characters are saying, you’re looking at the meaning behind the words. At what they’re not saying.

On getting stuck

Every single project I’ve ever worked on, I’ve got to a point where I think, ‘I can’t resolve this.’ Or, I’ve finished it, and I don’t like it. I’ve finished but I’m too embarrassed to show anybody. It just happens every single time. I don’t think there’s any project I’ve ever worked on where I haven’t at some point looked at it in despair, thinking, ‘I have no idea what I’m going to do. I have no idea how I’m going to resolve this.’ Eventually, of course, you do.

top

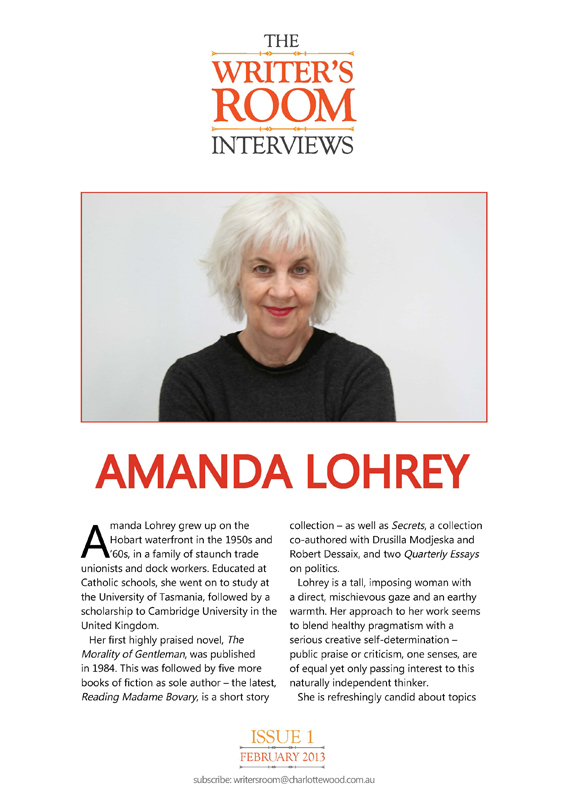

ISSUE ONE: AMANDA LOHREY

ISSUE ONE: AMANDA LOHREY

Amanda Lohrey grew up on the Hobart waterfront in the 1950s and ‘60s, in a family of staunch trade unionists and dock workers. Educated at Catholic schools, she went on to a scholarship to Cambridge University in the United Kingdom. Her first novel, The Morality of Gentleman, was published in 1984 to great acclaim. This was followed by five more works of fiction — the latest, Reading Madame Bovary, is a short story collection — as well as Secrets, a collection co-authored with Drusilla Modjeska and Robert Dessaix, and two Quarterly Essays on politics. Lohrey is a tall, imposing woman with a direct, mischievous gaze and an earthy warmth. Her approach to her work seems to blend healthy pragmatism with a serious creative self-determination —public praise or criticism, one senses, are of equal yet only passing interest to this naturally independent thinker.

On focus

When I begin work I need to have nothing else I have to think about. Nothing. I remember when I was young I heard Elizabeth Jolley give a talk where she said, ‘You young feminists probably won’t understand this, but if there’s the slightest difficulty happening in the family I just can’t work.’ But we did understand. I think women are very porous; they are all the time taking in what’s around them. Perhaps even more than men they need to shut off and have that ruthless focus that, traditionally, they’ve not been permitted.

On inspiration

I’m never inspired. You hear writers on panels saying, ‘Oh, the character just took me over and it just flowed through me,’ and I think, I have never, ever had that experience. Ever. Not for five minutes. Now, it might be because I’ve got a critical brain and have had a rigorous intellectual training. Maybe I’m overcritical, maybe I think too much, maybe I self-edit to a counterproductive degree — but, whatever, this ‘taking over’ process has never happened to me. Surprise developments, yes, but that’s different.

On tone

For me it’s about tone and rhythm. In books on writing there is too much emphasis on plot and characterisation and not enough on the more intangible elements. The most important thing is to find the voice, find the tone, establish the inner rhythm, the momentum that carries the thing along. You know, you’re in a bookshop and you pick up a book and straightaway you know if you’re going to be able to read this writer. You don’t care what it’s about, it’s just coming at you and drawing you in. It can be hard to define why, but I think it’s tone and rhythm.

On aesthetic forms

I’m drawn to the Platonic notion that there are ideal forms, that truth exists in a series of perfect forms and that whether we are artists or physicists we seek to explore those forms, to connect to that truth by aspiring to map or to emulate those forms. The closer we approximate them, the more revealing the work and the more satisfying. It’s that ‘aha’ moment we have when we experience a fully realised work of art. You have this sense of some perfect realm or sphere where everything comes together — it’s aesthetic satisfaction, and no-one I’ve read has ever successfully defined what that means. We just know it when we experience it.